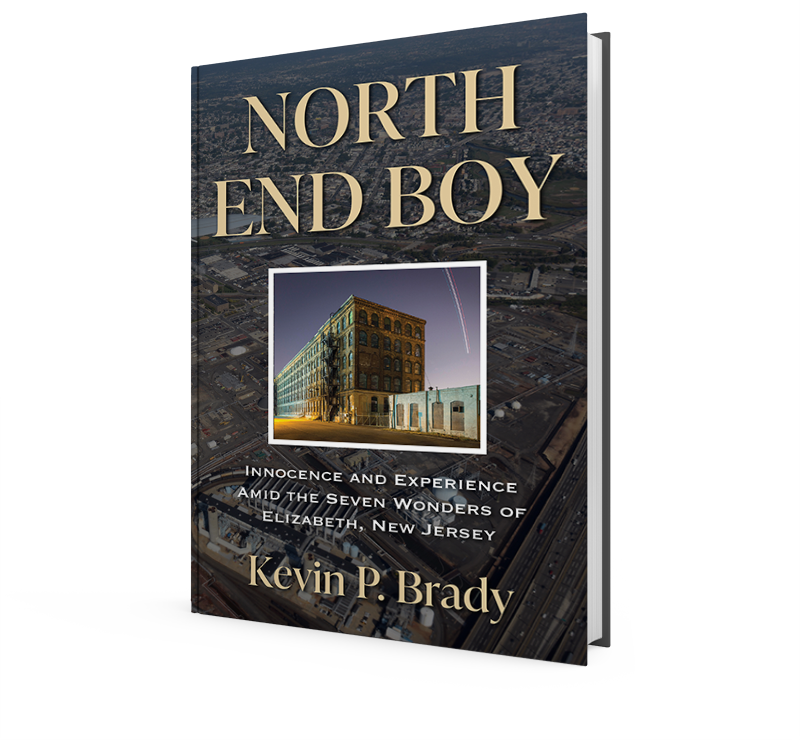

Innocence and Experience Amid the Seven Wonders of Elizabeth, New Jersey

It’s the summer of 1978. A time of great turbulence in the country, the city of Elizabeth, New Jersey, and the lives of seven young men. Social and economic crises abound with no end in sight. Rising crime, race riots, inflation, high unemployment, political corruption and the demise of manufacturing were crippling America, its cities and towns, and the people residing within them.

Although a worrisome period in history to come of age, a group of friends were enjoying their early 20s with few ambitions and fewer responsibilities. Then, over the inconceivable course of just 36 hours, the boys are thrust from advanced adolescence to the jarring realities of adulthood. The tragic loss of one of their own shatters the lives they knew and the dreams they held. Life changing decisions about families, careers and, ultimately, their destiny are made overnight. One embraces the family business. One moves out to California. One finds redemption in the Catholic Church. Another one doesn’t. The bond that held them all together becomes untethered.

During this period of time, it is not only the friends aging, but also the city of Elizabeth. The decline of its factories and local businesses, such as Singers Sewing Machine Works, Burry Biscuits and the Bayway Refinery, along with the development of new transportation routes like the Bayway Exchange, are destroying neighborhoods and livelihoods. Amidst this decay, police, politicians and mobsters all fight for the scraps and souls left in the wake. As Elizabeth crumbles, the friends struggle to find their place in the city and the world.

Loosely autobiographical, North End Boy is a meditation on urban America, as seen through the eyes of a young man with immigrant sensibilities and working-class roots. Local history buffs, as well as those with ties to Elizabeth, will be drawn to the landmarks and historical references peppered throughout the book, particularly the city’s seven wonders – Burry Biscuit factory, Bayway Refinery, Goethals Bridge, Singers Sewing Machine Works, the courthouse, New Jersey Turnpike and Newark Airport – and the roles they played in Elizabeth’s rich history.

Reading from the Author, Kevin Brady

Click play below to listen to the introduction of North End Boy.

CHAPTER 1 – The Courthouse

“How about a ride, Joe?” – Butch Mahon

“Get bent.” – Joe Ball

To the north, Newark Airport and the Burry Biscuit factory, which alone covered five city blocks. To the south, the Bayway Refinery and next to it the Goethals Bridge, which connected his city to the Isle of Staten. To the east and straight down Elizabeth Avenue, the New Jersey Turnpike and the massive Singer factory, purveyor of sewing machines to the world and almost a city in itself. Together, they made up the seven wonders of Elizabeth, New Jersey.

But none of them impressed Joe Ball, who patrolled the ethnic neighborhoods that lay among the seven wonders: Polish Bayway under the bridge, Italian Peterstown north of the refinery, the Cubans who fled Castro to settle on Elizabeth Avenue under the Turnpike, the more recent Black and Hispanic immigrants who battled it out in the shadow of the great sewing machine works, the polyglot North End between the airport and giant biscuit factory.

Joe made it his business to know each of these tribes and the streets that defined them. He knew the Polish refinery workers, the DeCavalcante family, who ran the rackets out of Peterstown, the cops in the North End, the shop owners on Elizabeth Avenue, drug dealers everywhere. After twenty years on the job, Joe had deliberately chosen not to rise within the ranks, preferring instead to work the streets as a lowly patrolman. His beat covered the bars, the gambling dens, the cat houses, and anything else in need of protection. Cops who knew and saw such things could be paid not to see and know them. And patrolman Joe Ball saw everything.

Joe was off-duty, on his way home from a card game run by the DeCavalcante’s, where he provided the muscle. About fifty, stoutly built and bullet-headed, he looked every inch the veteran non-com that he was. At the age of eighteen, Joe had volunteered and served with the Third Army in Patton’s madcap dash across Europe. Like many survivors, Joe never discussed the war. He kept a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart hidden in a cigar box at the back of his bedroom drawer. The war and the peace that followed left indelible marks on the young person of Joe Ball. The war sharpened him. The peace gave him confidence — and for good reason.

Immediately after the war, the United States accounted for 50 percent of world GNP, three times the size of the combined Axis powers and four times the size of the Soviet Union. The U.S. owned 66 percent of the world’s productive capacity and 70 percent of all automobiles. Los Angeles had more cars than Asia. Americans owned 80 percent of all electrical appliances on earth. With only five percent of the world population, Americans possessed more wealth than 95 percent of the rest of the world. The U.S. dollar was the only reserve currency worth holding. Americans had won, and they had won big. War reparations? Why bother?

As the last men standing far above a war-ravaged globe, it seemed pretty clear to American leaders that the whole place needed to be re-built. With a peace dividend burning a hole in their pocket, can-do Americans set about re-constructing the world in the only way they could: in their own image and likeness. The Marshall Plan created democratic Mini-Me’s in Europe and Japan — but not the Soviet Union, which had its own notions about the pursuit of happiness.

By 1978, however, deep questions began to trouble the likes of Joe Ball. A stalemate in Korea, two Kennedy assassinations, the killing of Martin Luther King, a humiliating loss in Vietnam, a generation gap, race riots, a Nixonian landslide followed by a Nixonian collapse, high interest rates, dollar devaluation, gas lines, stagflation, an indifferent stock market, rising crime – all these conspired to shake the confidence of the greatest generation. Newly aggressive Communist foes challenged a crippled America and threatened to re-write the ending to World War II. Freedom itself seemed to be losing out to a new breed of totalitarians who controlled more and more of the earth’s surface.

Thus came doubt into the mind of patrolman Joe Ball.

Traffic was unusually light for 9:00 in the morning at the corner of Broad Street and Elizabeth Avenue, the Times Square of the city. So when an unlikely kid in a brilliant, brand new, red ‘78 Cadillac stopped next to him, Joe rolled up for a closer look. He leaned over and immediately recognized Butch Mahon through the sealed windows of the air-conditioned Caddy.

Butch was an unpleasant piece of business. Although he went to St. Catherine’s School with Joe’s kids in the North End, he really belonged in reform school, if there. He managed to hang in because his mother worked BINGO, fairs, and a million other odd jobs that kept the place going. The twenty-five-cent seat money and single dollar that each family dropped into the collection basket helped, but the volunteers, both lay and clerical, formed the beating heart of the parish. It took all of them to preserve Butch’s shot at redemption.

In addition to the parish, the archdiocese of Newark, and arguably the Pope, all of whom were fighting to save the soul of Butch Mahon, there were a number of secular authorities trying to salvage his civic life. As a resident of the over-governed state of New Jersey, Butch frequently tangled with all the branches of city, county, state, and federal law enforcement, none of which had any measurable effect on his distinctly uncivil behavior. Despite the combined efforts of church and state, Butch could not avoid his destiny as a low-level thug. Butch, the delinquent youth, turned into Butch, the felon, with the inevitability of the seasons. After eight difficult years in parochial grammar school, the Dominican nuns released Butch into the greater wilds of Elizabeth with a mixture of relief, concern, and a healthy measure of old-fashioned Catholic guilt at having failed young Butch.

Joe tapped the horn of his ‘71 Chevy and got Butch’s attention. Butch scowled even when asleep. Aroused, his rubbery face twisted this way and that, following the erratic impulses of his overwrought brain. On recognizing patrol-man Joe Ball, his dull narrow eyes opened wide in fear. He considered making a run for it. His mind bounced between the animal poles of flight and fight. The Cadillac was, of course, stolen, and the brief, violent, pointless life of Butch Mahon passed before him. He gripped the steering wheel and prepared to floor the Caddy. He was sure he could outrun and out weave Joe’s Chevy through the downtown streets of Elizabeth. Old Joe Ball might not even chase him. Joe stuck his hand out and casually signaled for Butch to roll down his window.

“Running a few errands, Butch?” asked Joe.

“No, Mr. Ball, I mean Officer Ball. No,” stammered Butch.

“Pull over and get in.”

Butch turned right onto Broad St. and parked the Caddy.

Something in the calm demeanor of the street cop, something in the easy way he motioned for Butch to pull over, re-assured Butch and told him that he should not run, that there was another way.

“Where are you taking the Caddy?” asked Joe.

The question implied what they both knew. At twenty-three, Butch was too old to be joy riding around town at nine o’clock on a Friday morning. This was business. The car was destined for a chop shop, where it would be cut into a hundred pieces within the hour and dispatched into the aftermarket. The only question was where.

“North End.”

“McClellan Street?”

“Yeah.”

“Let’s go.”

“You’re coming with me?”

“Yeah, I know them.”

Butch relaxed. Joe Ball knew the chop shop and that seemed to be a good thing, a safe thing. Joe would even escort him to his destination. Butch got back into the Cadillac and slowly cruised down Broad Street, under the railroad arch and onto the familiar streets of the North End. They stopped at the red light on North Avenue. Both looked up and to the left at the flashing sign over the bank to check the time, a ritual for everyone who passed this way:

9:15

July 21

90 degrees

The bank clock didn’t convey the humidity, about 90 percent. Nor did it convey the sensation of breathing in the used-up industrial exhaust of Elizabeth at the height of summer. Across the street on Newark Avenue, the day shift had begun at the Burry Biscuit factory. The sickly-sweet aroma of strawberry Scooter Pies (universally reviled in the North End) further thickened up the ozone.

As they drove, Patrolman Joe Ball considered his options. He had Butch dead to rights. He could let Butch go and receive a deposit in his favor bank, a small deposit from a bit player destined for prison, which was worth almost nothing. Or he could play out this little drama and possibly get a larger deposit from the chop shop, maybe even a little cash. And who knew what might come after that? More dangerous, perhaps, but probably worth it. He didn’t really know the guys who ran the chop shop — but what of it?

The favor bank was real cop stuff, something deeply embedded in the job, closer to their blue hearts than the right to overtime or funded pensions. All cops kept track of favors given and favors received from fellow cops. Every cop stored up these favors in his private account and knew exactly what every other cop in the world owed him. The favor bank issued unprinted currency for cops, currency that could only be spent by cops on other cops. But the favor bank was more real, and probably more valuable, than legal tender. It also provided a backup system of justice when the everyday system up in the courthouse failed, and so helped to keep the earth from spinning off its axis. The difference between the favor bank of Joe Ball and that of other cops was that Joe extended credit to criminals.

Joe followed the Caddy to a gas station, which was unusually busy. The garage door opened and both cars entered. Joe and Butch got out of their cars, and the door came down behind them.

“Who are you?” said a worker, who looked Joe up and down and detected the cop lurking beneath the plain clothes.

“Where’s the owner?” said Joe.

“Inside,” said the worker, with a nod to the office.

Joe walked into the office. The walls were covered with girly calendars from the previous ten years. The desk was piled high with neglected customer invoices from the same period, a sure sign of an all cash business.

“I ran into a friend on my way home, the guy who brought in the Caddy,” said Joe. “I made sure he got here okay.”

“Thanks,” said the owner, who reached into his pocket, peeled off $ 300 from his wad and handed it to Joe. “For your trouble.”

“No trouble.”

“No more after this, right?” said the owner, who still held onto his end of the cash.

“No more.”

The owner released the bills, and Joe slipped them into his pocket. An understanding had been reached. The money was a tip for services rendered, not the prelude to a larger shakedown. Joe would stay quiet, and the owner would go about his business of relieving traffic on the streets of Elizabeth, presumably under the protection of someone further up the chain. The peace would hold.

Out in the garage, Butch realized he was miles away from home and his ride was about to be sold for parts, a thought that had not occurred to him when he drove in. Flush with cash and feeling good about his recent caper with Joe Ball, an obvious solution presented itself to Butch.

“How about a ride, Joe?”

“Get bent.”

Joe decided he needed some sleep, so he headed back to his home just a short drive away on Sheridan Avenue. His wife sat at the kitchen table reading The Daily Journal, chronicler of all things Elizabeth. She looked up at him, placed her finger on the paper to hold her spot, and greeted him from behind her reading glasses. Their boys were stirring, each of them in various stages of morning, noon, or night, depending upon their schedule. The entire family kept all hours. They were in this regard very much like their father.

“Billy up yet?” asked Joe, taking his seat at the kitchen table.

“It’s Friday. He’s off,” reminded Mrs. Ball, removing her finger, and dropping her head back into the paper.

Billy was the oldest of three very big, very scrappy, similarly bullet-headed boys, none of whom possessed an ounce of athletic ability. But they did love to fight. Billy was the biggest and the most lethal brother. Once in a fight, Billy gained a kind of mutant strength that intensified until he crushed his adversary. He also possessed an uncanny ability to identify an opponent’s weakness, a useful trait in the bars where he bounced. Just a week ago, he ended a fight by sticking his fingers into the oversized nostrils of a misbehaving patron and hurled him out into the street by his nose. All of this was common knowledge inside the Ball household and most of the North End. As a result, Billy was a frequent victim of the un-telegraphed sucker punch, his only known weakness.

The Ball brothers spent much of their time stress-testing each other. But they all agreed on one thing: they were catching up to their father. In their youth, patrolman Ball was a street legend full of swag and stories, capable of taking them all, which he did regularly. Now, the boys got their own swag and the old man’s stories were starting to run together. He was still a presence, just not an icon.

The middle son was eating cereal, while his younger brother fried up a burger with onions. Billy entered the kitchen, sized up the situation, and opted for the cereal. Four melon-headed bodies bobbed around the kitchen, retrieving plates, spoons, milk, salt, pepper, ketchup, sugar, coffee and soda, eggs or meat, depending on whether they were eating breakfast, lunch or dinner.

“Ran into Butch Mahon this morning,” said Joe.

The two brothers looked up from reading the back of their cereal boxes. Mrs. Ball placed her finger on the newspaper. A plane landing at Newark Airport roared overhead. It seemed inches away from the roof and shook the house down to its studs. This happened whenever the wind shifted out of the north and the planes needed to fly over Elizabeth to land safely. Like all Northenders, Joe reflexively raised his voice a few decibels to be heard.

“CAUGHT HIM IN A HOT CADDY. RIGHT ON BROAD STREET,” shouted Joe.

“YOU LET HIM GO?” yelled Billy.

“YEAH.”

This was hardly news. The boys returned to their cereal boxes and Mrs. Ball removed her finger from the newspaper. The plane landed. Joe lowered his voice and tried again.

“So, Billy, what are you doing today?”

“Meeting the boys tonight at the K Tavern. Going into the city with Jackie now.”

“What for?”

“Don’t know yet. We’ll find something.”

This was true. Billy Ball and Jackie Martin had been close friends since their school days together at St. Catherine’s. Whenever they got together, things just happened, often the most improbable things. Like the time as kids they walked every floor of the all-Black, always dangerous, Dayton Street projects to retrieve their stolen bicycles and miraculously emerged unscathed. Or the time they managed to get a moving violation inside of a car wash. Or the time they ran into each other on a long-range patrol in the jungles of Vietnam. Jackie Martin was the de facto fourth brother in the Ball home, and Billy extended to him the same bouncer-like protections he gave to the rest of the family. They would undoubtedly find something to do in New York City. The thought of tacking on a few beers with the boys at the K Tavern made the next twelve hours even more appealing.

The familiar car horn of Jackie’s Pinto beeped in the driveway. Billy got up from the table to go. He walked past his younger brother at the stove and took a rabbit punch to the back of the head, which knocked him forward a step. Billy dipped his shoulder, plowed into his brother, and pinned him against the counter. From this position of moral superiority, Billy pounded the back of his brother’s head with a flurry of roundhouses. The hamburger, the onions and several dishes crashed to the floor.

“Out of my kitchen,” said Mrs. Ball above the din. “Joe, get my spoon.”

The spoon. Mrs. Ball wielded the long wooden spoon as both weapon and gavel. She took it and whacked them both until the boys ceased hostilities and they all began to laugh. When it was over, the three of them stood panting and grinning at each other, amused at their absurd, predictable selves

“I’m going to turn in,” said Joe, stretching his arms over his head.

ABOUT THE

AUTHOR

Kevin P. Brady is a North End boy himself. He was born and raised in this working-class neighborhood of Elizabeth, New Jersey, where his Irish immigrant parents settled after World War II and hasn’t strayed far since. He and his wife, who is from adjacent Newark, raised their family within five miles of their hometowns, allowing him to witness the tides of change the city has undergone throughout the decades. Those changes, and their impacts on Elizabeth’s residents, are the subject of Kevin’s first book, North End Boy.

All Book Sale Proceeds to Benefit St. Benedict’s Preparatory School

All proceeds from the sale of North End Boy will be donated to St. Benedict’s Preparatory School in Newark, New Jersey, which is featured in the book. St. Benedict’s prepares boys and girls to fulfill their potential as emotionally mature, morally responsible and well-educated citizens. Operated by the Benedictine monks of Newark Abbey since 1868, St. Benedict’s offers a rigorous curriculum that sharpens the mind, shapes the character and nourishes the spirit.